Leading by Design: Laurie Olin

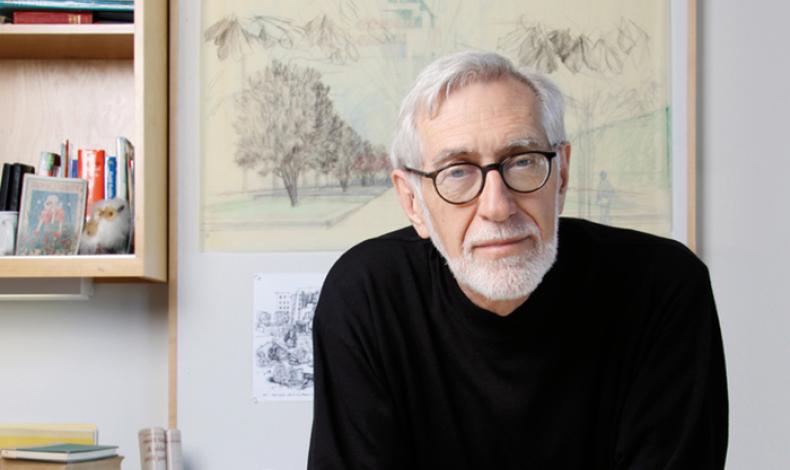

Laurie Olin, professor of practice emeritus in landscape architecture at PennDesign, talks about the exhibition and the process of drawing.

Leading by Design explores the work of PennDesign alumni, faculty members, and supporters of the School who are expanding the practice of art and design to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

Since the beginning of October, the Kroiz Gallery at the Architectural Archives has been exhibiting decades of sketches and drawings by Laurie Olin, professor of practice emeritus in landscape architecture at PennDesign and a 2012 winner of the National Medal of Arts. Through his Philadelphia-based design studio, Olin has completed prominent landscape projects across the world, including the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, Bryant Park, and Battery Park City in New York; Apple Park and the J. Paul Getty Center in California; and the U.S. embassies in London and Berlin. He has taught at PennDesign for 42 years.

In November, Olin sat down in the Architectural Archives to talk with Design Weekly about drawing, writing, designing, and teaching. The conversation has been edited for clarity and split into two parts. In Part 1, Olin talks about the exhibition and the process of drawing. Olin’s drawings are on display in the Kroiz Gallery through December 21.

I want to talk about the drawings first. Is this the first time your drawings have been exhibited?

No. Back in the sixties and seventies, I exhibited and showed stuff and sold it. I just couldn’t make a living at it, but I was successful. That was in Seattle, and that was a long time ago. I dropped out of architecture, and I had not ended up back in design and landscape architecture. And so I was living and writing and drawing and painting, and I did a lot. A lot of the drawings in here are from between 1969 and, probably, 1974 or so. But then every so often there would be a whole other batch. So no, I’ve exhibited and shown and so forth, but I haven’t for a long time. This is the first time in, I don’t know, 20 years or so.

I had a bit of a chance to look at some of the the sketches that are posted here, and I wonder, are there certain kinds of places that you find yourself wanting to draw more than others?

Are there certain places? Well, yes. Parts of the natural environment attract me very much. And there were places that I wanted to live, and so therefore you draw where you are. I was very interested in certain social aspects of our cities, so I’ve drawn a lot in places like Skid Road in Seattle and in cities and markets and places like that. I’m very fond of the wilderness, but also, a preoccupation of modern poetry and art has been ordinary life. And so I spent a fair amount of time just looking at and drawing and documenting what you might call middle-class, bourgeois, ordinary settings, too, as an interest in: Who are we? What is this all about?

Can you talk a little bit about how you do the drawing? Are you trying to sort of recreate something you’ve seen? Or are you trying to explore something that you’re trying to see more clearly?

Well, it depends on the day. It depends on the mood, but sometimes you just try to record something that’s of interest. Like, “Oh, that’s interesting.” Or, “How does that work?” And so it’s about seeing and recording what you see, and trying to look very carefully for an understanding that might come from the study of looking at something. But once you start drawing, the drawings have a life of their own. And sometimes you draw it just for the sheer pleasure of it. It’s good to go out, and you don’t know what you’re going to do—you just do something. And once you start and you see what you’re going to do that day, you never know. At least I don’t.

A lot of design is about planning and thinking and then working through a problem. Drawings are problems that you set for yourself when you’re trying to figure out how to express something. And sometimes you’re trying to record the way a thing is made, how it’s constructed. Sometimes you’re trying to record the spirit of something, and that’s a very different kind of drawing.

Is it something that actually helps you experience the thing that you’re experiencing?

Yeah, sure. Because drawing makes you sit still and be somewhere, and you learn from looking. You know, our eyes aren’t a separate organ. They’re not like your liver or your kidneys. They’re actually a part of the brain that hangs out through two holes in the head. There’s this skull that has these holes, and these highly specialized pieces of the brain stick out of it and take in information directly into the brain.

And so seeing is actually part of being conscious and thinking. A lot of our brain is devoted to processing that information. And so drawing is an extension of seeing, in a way, for me, and I think for many people who draw … It’s forcing yourself to see in particular ways, and some of them are very gestural, and some of them are very detail-oriented. Some of them are factual, and some of them are more spiritual.

There’s different kinds of drawing. You start somewhere and do something. The thing about drawing, and why it’s related to seeing so much, and thinking and feeling, is that you look at the world and there’s all this information. Tons of information. Too much. Which is the problem with the camera—it’s kind of indiscriminate. The brain is discriminate. So when you look at things, you see all this information and you begin to sort it and decide which information is useful. Then you look at the piece of paper and there’s nothing there. Zero. Then you say, well, I’m going to put down these pieces of information that I’ve just sorted from all the others.

“A lot of design is about planning and thinking and then working through a problem. Drawings are problems that you set for yourself when you’re trying to figure out how to express something.”

Are there things that you would draw, spaces that you would like to go to to draw, that you haven’t gone to?

Sometimes you just want to go back to the same place, and try it again and try and do a better job or say, “Well, what else? How else could you do it.” But it’s not a touristic thing where you want to go check out stuff just for drawing. The drawing usually comes as a function of being somewhere, and appreciating it. Sometimes I’ll set off, and I’ll think, “I want to go down to the beach and draw,” or “I want to go into the woods and draw.” But then I usually don’t know what I’m going to do until I get there. You see what’s around. Then you think, oh, it’s hot or it’s cold or there’s nowhere to sit and you think, “What should I do?”

Very often outdoors, drawing is done sitting down, so you put things on your lap, no matter how big they are. That’s great. I kind of like the just going out. You put the stuff in the bag, or under your arm and you set off. You don’t know what you’re going to do. You go into the world, and you find “it” somehow, and then you see things that are of interest. “What are these people doing here? Look at that.” And then you just draw.

Have you ever discovered anything that you didn’t expect through that process?

All the time. It’s hard to explain because the drawings afterward always seem so inevitable or logical, or yes-of-course, but when you begin, that’s not true. Why would you draw that birch tree? Where I grew up, there were a lot of birch trees. So, one day I did a birch tree, because it seemed like the thing to do, and it wasn’t bad. Well, at the time it was pathetic, because the birch tree was so beautiful, and the drawing was so simple. But later the drawing had some spirit to it.

Anything else you want to say about drawing?

Drawing is a human act that’s one of the oldest there is. It’s one of the oldest arts. It’s a toss-up between music and drawing, which is older. We’ve got them both back to about 40,000 years or so. They’re pretty fundamental in terms of spirit and of making a mark and being in the world.

Drawing for me is an enormous pleasure. It’s a gift to be able to sit calmly and study the world and then to make drawings. It’s an enormous pleasure. And it gives other people pleasure, which is interesting. But I always find that you look at the world, and it’s so rich, and you make a drawing, and you look at the drawing, and it’s so poor. At the time you finish it, they’re very disappointing. They’re never quite good enough. Then an hour later, they don’t look so bad. And a year later they’re a record of the world. Drawings have a strange career of going from being failures to being interesting things.

Photo credit: © OLIN / Sahar Coston-Hardy