Barton Myers Donates Papers to Architectural Archives

By the time Barton Myers (MArch'64) founded his own practice, he’d already been an architect in the office of Louis Kahn in Philadelphia, an Air Force fighter pilot stationed in Europe, a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, and a young boy fascinated by Jeffersonian architecture in Norfolk, Virginia.

By the time Barton Myers (MArch'64) founded his own practice, he’d already been an architect in the office of Louis Kahn in Philadelphia, an Air Force fighter pilot stationed in Europe, a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, and a young boy fascinated by Jeffersonian architecture in Norfolk, Virginia. He brought all of that experience with him to Toronto, which in the late 1960s, he says, seemed like “the new Chicago or New York, or the combination of Chicago and New York.”

“I looked around at all this incredible steel building going up, and nobody was using it,” Myers says. “The architects were covering it all up.”

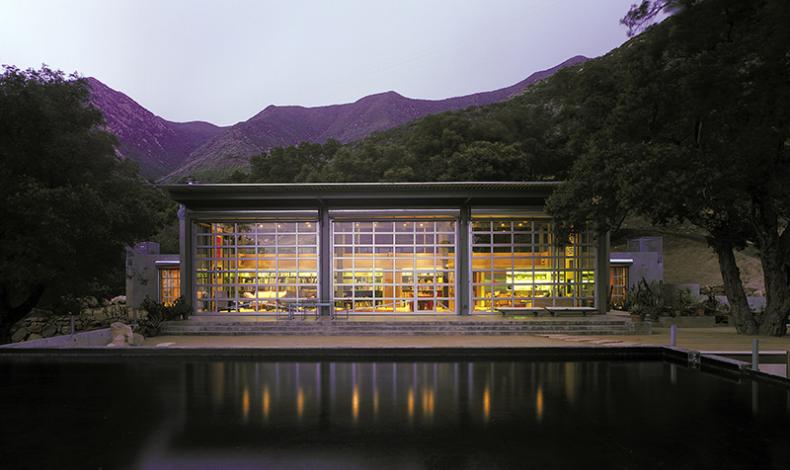

Myers co-founded the practice of Diamond and Myers in Toronto in 1968, then struck out on his own in 1975, before eventually moving his firm to Los Angeles in 1984. Today, Myers is recognized as a pioneering architect and urbanist, with his personal residence in Toro Canyon counted among the “masterworks” of American home design and numerous awards to his name, including a Gold Medal Award from the American Institute of Architects Los Angeles, the chapter’s highest honor. It was in Toronto that Myers developed his architectural philosophy built on responding to urban context, pioneered the use of steel in residential housing design, and completed his first designs for performing arts centers, which became the hallmark of his later career. And this year, Myers has agreed to donate an important collection of records from that fertile decade-and-a-half in Toronto to the Weitzman School’s Architectural Archives, adding new depth to the Archives’ holdings.

“It’s going to be interesting someday to look at the work and see the beginnings of stuff in Toronto, and then the more sophisticated, more mature work out in Los Angeles,” says Myers.

Many of Myers’s papers are already held at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum at UC Santa Barbara, near his iconic glass-and-steel Toro Canyon home, which he sold earlier this year. The Museum organized a 2014 exhibition of Myers’s work that was also presented at the Architectural Archives’ Kroiz Gallery. Penn and UC agreed to collaborate in preserving the Myers archives.

“For people on the practitioner side, the archives provide a chance to go back and look at the architect’s sketches and original drawings to understand their thought process,” he says. “For people who are interested in history, the archives really give you a chance to see what it was like to be an architect, what forces you’re dealing with, and how one functions in a certain time and context.”

Although the Architectural Archives holds a number of Myers’s drawings from his time in Kahn’s office as part of the Kahn Collection, the new records will deepen the Archives’ collection of material from the Kahn era. Sketches of Myers’s earliest theater designs in Canada should also interest practitioners learning the intricate needs of multi-functional performance spaces, says William Whitaker, curator and collections manager at the Archives.

“We can play a role in recognizing that Barton’s collection is of national and international significance,” Whitaker says. “We wouldn’t be taking the collection were it not that our students could learn something from it. There are lessons within his example that I can bring to students, and that relates to the creative process, and how one integrates incredibly complicated systems into built works.”

Myers says that he developed a fascination with big steel machinery at the Naval Academy and in the Air Force. But he knew that he didn’t want to remain in the Air Force, and that his wife, Vicki, didn’t want to be “an Air Force wife.” The destruction of historic fabric in Norfolk during the Urban Renewal period of the mid-20th century also sparked a passion for preserving urban environments.

“I was ripe for Penn,” Myers said. “I hated what happened [during Urban Renewal], and Penn offered me a future of how you could love cities, and respect the past, and help them, but also do great new things.”

Myers says his time at Penn was an “unbelievable period,” and the campus itself “an amazing, utopian, urban city.” Teachers like Kahn, Ian McHarg, and Holmes Perkins, who served as dean from 1951 to 1971 and founded the Architectural Archives, encouraged students to see the city as an extension of the classroom, Myers says. Because of that education, he and the other designers at his firm were “very principled architects.”

“We weren’t trendy, and we were all very interested in the context,” Myers says. “I think my ideas have always been pretty strongly in urban conservation and infill housing, trying to use what you can before you tear it down. And that all came out of Penn."

Myers was belonged to a cohort of alums that elevated Penn’s status in the design world, Whitaker says.

“This was a time when the faculty and the students here were asking serious questions about what architecture and planning and landscape ought to do, and redefining what it is that those fields would do,” Whitaker says. “They wanted to see them much more engaged with issues of equity and history and ecology. It was a more expansive and redefined modernism—more inclusive of factors outside of abstraction.”

Vicki, who served as the chief financial officer for Barton Myers Associates, died last year after 60 years of marriage. She was “the smartest woman I ever met,” Myers says, and her musical education — she was a pianist who graduated with a degree in music from Penn — influenced his work on performance spaces. After she died, Myers sold their home in Santa Barbara and moved to Connecticut, where his daughter lives. At 86, he’s still working on theater designs, and the long-awaited Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts in Orlando, which he worked on, is nearing completion.

Whitaker says he wouldn’t be surprised if Myers is hoping for yet another theater commission. In his career, he has treated each job as an opportunity to sharpen his ideas, an approach that students should be able to learn from in his archived works.

“If you get another shot, you can continue that sense of refinement, and I really appreciate that about him,” Whitaker says. “You can see that by looking at his interest in the steel house, his interest in urbanism, his interest in theater. It’s yet another opportunity to refine, to deepen one’s critical understanding of these things. That’s inspiring. It’s inspiring to students, and I think to professionals, too.”